Summary

This is a story about the most elusive and sinister software bug I ever came across in my decades-long career as a programmer.

The setting

At some point early in my career I was working for a company that was developing a hand-held computer for the area of Home Health Care. It was called InfoTouch™. The job involved daily interaction with the guys in the hardware department, which was actually quite a joy, despite the incessant "It's a software problem!" -- "No, it's a hardware problem!" arguments, because these arguments were being made by well-meant engineers from both camps, who were all in search of the truth, without egoisms, vested interests, or illusions of infallibility. That is, in true engineering tradition.

The manifestations

During the development of the InfoTouch, for more than a year, possibly two, the device would randomly die for no apparent reason. Sometimes it would die once a day, other times weeks would pass without a problem. On some rare occasions it would die while someone was using it, but more often it would die while sleeping, or while charging. So, the problem seemed to be completely random, and no matter how hard we tried we could not find a sequence of steps that would reproduce it.

When the machine died, the only thing we could do was to give it to the hardware guys, who would open it up, throw an oscilloscope at it, and try to determine whether it was dead due to a hardware or a software malfunction. And since we software guys were not terribly familiar with oscilloscopes, we had to trust what the hardware guys said.

Luckily, the hardware guys would never say with absolute certainty that it was a software problem. At worst, they would say that it was "most probably" a software problem. What did not help at all was that one out of every dozen times that they went through the drill, they found that it did in fact appear to be a hardware problem: the machine was just dead; there was no clock, no interrupts, no electronic magic of the kind that makes software run. But what was happening the rest of the times was still under debate.

This situation was going on for a long time, and we had no way of dealing with it other than hoping that one day someone either from the software department or the hardware department would stumble upon the solution by chance. The result was a vague sense of helplessness and low overall morale, which was the last thing needed in that little startup company which was struggling to survive due to many other reasons having to do with funding, partnerships, competitors, etc.

The discovery

Then one day as I was working on some C code somewhere in our code base, I stumbled upon a function which was declaring a local variable of pointer type and proceeding to write to the memory location pointed by it without first initializing it. This is a silly little bug which is almost guaranteed to cause a malfunction, possibly a crash.

To this day still I do not know (or do not remember) whether that early version of Microsoft C did not yet support warnings for this type of mistake, or whether the people responsible for our build configuration had such hubris as to believe that "we don't need no stinkin' warnings".

I quickly fixed the bug, and I was about to proceed with my daily work, when I thought to take a minute and check precisely what were the consequences and ramifications of that bug before the fix.

First of all, I checked to see whether the function was ever being called, and it turned out that it was; however, the InfoTouch was running fine for 99.9% of the time, so obviously, due to some coincidence, this bug did not seem to cause any problems.

Or did it?

The astonishment

I decided to see exactly what was the garbage that the pointer was being initialized with.

The problem was in function cfunc(). Function cfunc() was invoked from function afunc(), which had just previously invoked function bfunc().

static void afunc()

{

bfunc( arg1, arg2 );

cfunc( arg1 ); // <-- function with uninitialized local variable

}

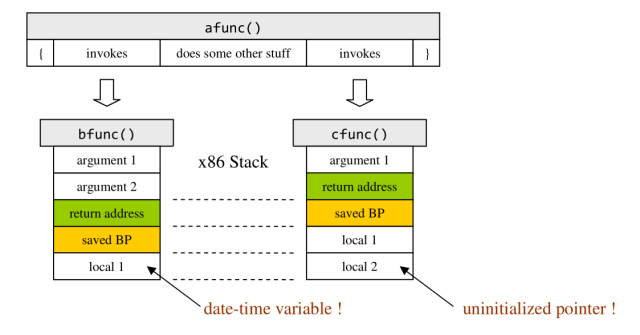

Function bfunc() had two arguments and one local variable . Function cfunc() had one argument and two local variables, of which the second was the uninitialized pointer. So, the uninitialized pointer in cfunc() shared the same stack word as the local variable in bfunc().

To my astonishment, I discovered that the local variable in bfunc() was a timestamp, where the function stored the current time.

This is how the stack looked:

So, the uninitialized pointer contained a bit pattern that represented a date and time. This resulted in random memory corruption during different hours of the day and different days of the month. The function was not being invoked very frequently, so the memory corruption was building up slowly, until some vital memory location would be affected and the software would crash. It is amazing that the machine ever worked at all.

After this bugfix the InfoTouch never again experienced any problems of a similar kind.

The lesson learned

What do we learn from this? Warnings are your friend. Enable as many warnings as you can, and use the "treat warnings as errors" option to ensure that not a single warning goes unnoticed.

Old comments

Unspecified 2015-12-14 13:11:39 UTC

nice story...

michael.gr 2015-12-14 13:39:21 UTC

Thanks, Divyesh! C-:=

Anonymous 2019-09-16 18:56:39 UTC

Classic :)